Introduction

Attackers are increasingly utilising QR codes in their phishing campaigns because they don’t just evade standard detection, they are incredibly difficult to detect without some significant effort.

A QR code (as I am sure most of the people reading this article are aware) is a type of barcode, which has become increasingly popular in day to day life. QR codes are everywhere now, on restaurant tables, on posters, advertisements, food labels, and many more. Perhaps their presence in every day life, increases the chances an unsuspecting user may not think twice about scanning one in an email. Personally, I think they’re suspicious, but I work in cyber security, I’m suspicious of everything that isn’t plain text.

There aren’t many statistics on QR phishing (dubbed as ‘Quishing’ by the community). One Securelist Kaspersky article suggests they have had their day. The article details how the number of detected phishing attacks declined to just 762 in August 2023, from a volume of over 5000 in June of the this year. However, a number of reputable sources in the community are suggesting that quishing is still on the rise.

What makes detection so difficult?

QR codes can translate to URLs which redirect to malicious websites, but in an email the link is not directly embedded. So unless your email system is employing some sort of preview email scanner with AI to detect QR codes, they are probably going to get through your email security filters.

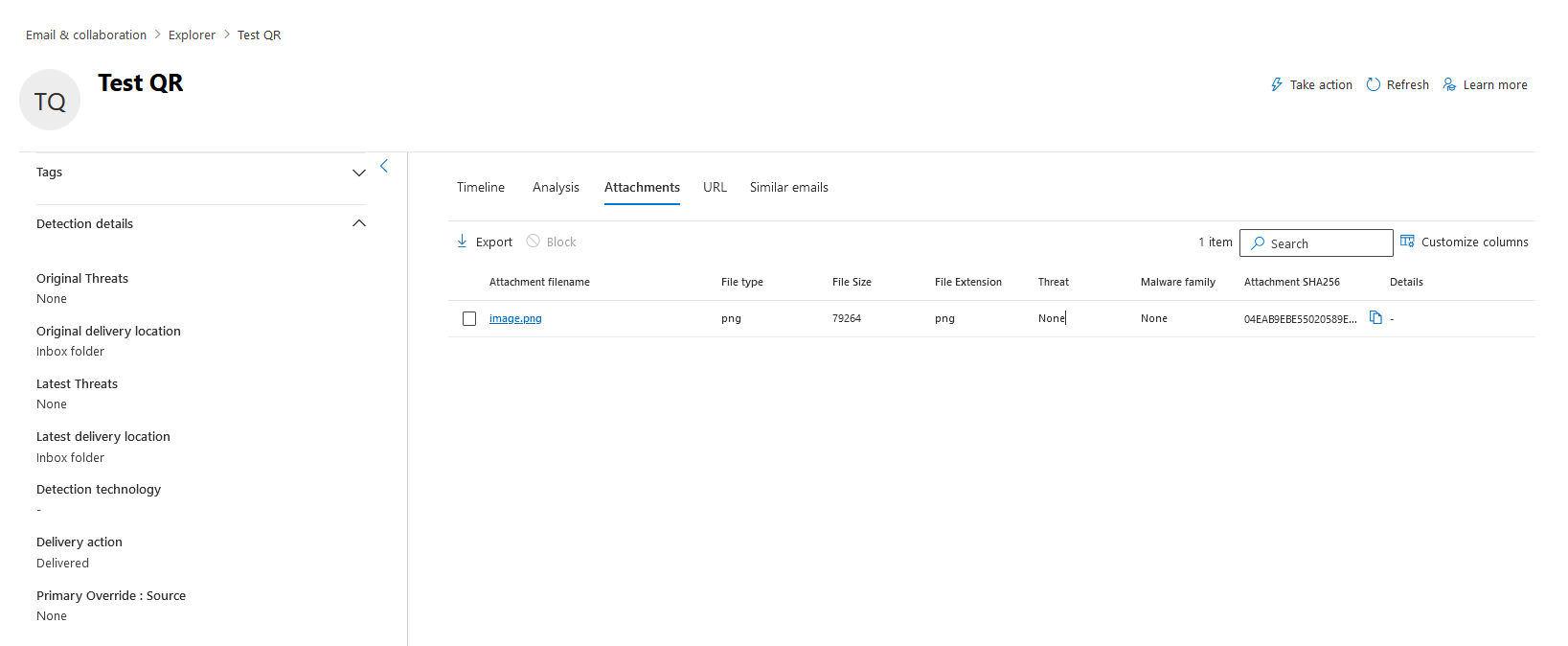

QR codes pasted into the email body do come through as “attachments” from what i can see in the Microsoft 365 Explorer.

So the good news is, you can safely determine that any QR code in an email is going to display as an email with an embedded image attachment in the logs. This gives us a starting point for detection.

A theoretical approach to detection

A little disclaimer before I get into this, you probably can safely detect a number of emails by using a KQL query which looks for attached image files, and some key words in the email subject such as “scan”, or “QR”, or “important”, but this isn’t foolproof. I want a method which tells me definitively that a QR code exists within an email message. Although the method detailed below is difficult to set up, likely impractical, and likely expensive, it will definitely identify QR codes in emails.

The concept

This concept works on the idea of a function application, which obtains the base64 encoded content of image files, from emails, by using the Microsoft Graph API. Then, by rendering the image from the base64 content, you can then perform analysis to determine if it’s a QR code. The whole process is triggered when an email with an image attachment is detected coming inbound in the email logs.

The detection rule

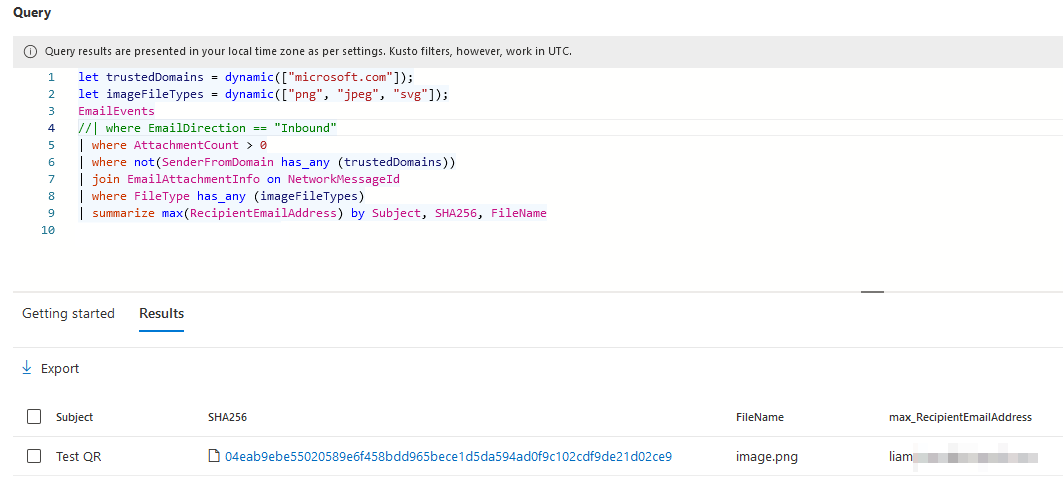

The detection rule is fairly straight forward. It looks for all inbound emails with attachments in the EmailInfo table, and then joins the EmailAttachmentInfo table to filter for the image attachments. You could jazz it up for your environment to not look at some trusted domains or something similar, but be cautious, the idea is we do not want to filter out too much so that we miss a QR code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

let trustedDomains = dynamic(["microsoft.com"]);

let imageFileTypes = dynamic(["png", "jpeg", "svg"]);

EmailEvents

| where EmailDirection == "Inbound"

| where AttachmentCount > 0

| where not(SenderFromDomain has_any (trustedDomains))

| join EmailAttachmentInfo on NetworkMessageId

| where FileType has_any (imageFileTypes)

| summarize max(RecipientEmailAddress) by Subject, SHA256, FileName

In my testing I have noticed that all images embedded in emails appear to be called “image00X.filetype”. It might be worth filtering the KQL to only look at these images as likely an attacker will not be attaching the QR code but rather embedding it. { : .prompt-tip }

Utilising the Graph API

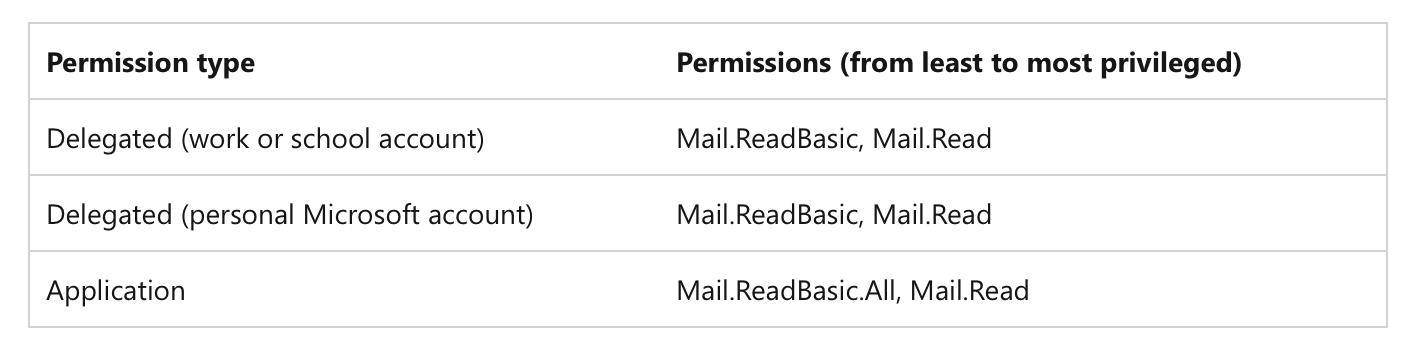

Permissions Required

In order to use the listed endpoints, you need a service principal with Mail.Read permissions assigned, as detailed in the Microsoft Documentation.

API endpoints

The graph API allows you to obtain messages programatically from your exchange server by using the Get Message API endpoint. The documentation for this endpoint can be found here.

As the documentation describes, you need a message id and a UPN in order to obtain specific messages.

1

GET /users/{id | userPrincipalName}/messages/{id}

Pretty standard stuff, although I can’t seem to find this message id anywhere but via the List Messages API endpoint. That’s really frustrating as I was hoping I could easily get the information out of an analytics rule, but still it’s not impossible to hack our way around this and obtain that id using the List messages API.

The list messages API uses a UPN too, so our detection rule above should contain all the info we need to start using the API. In order to obtain the ID I have filtered by using the subject line.

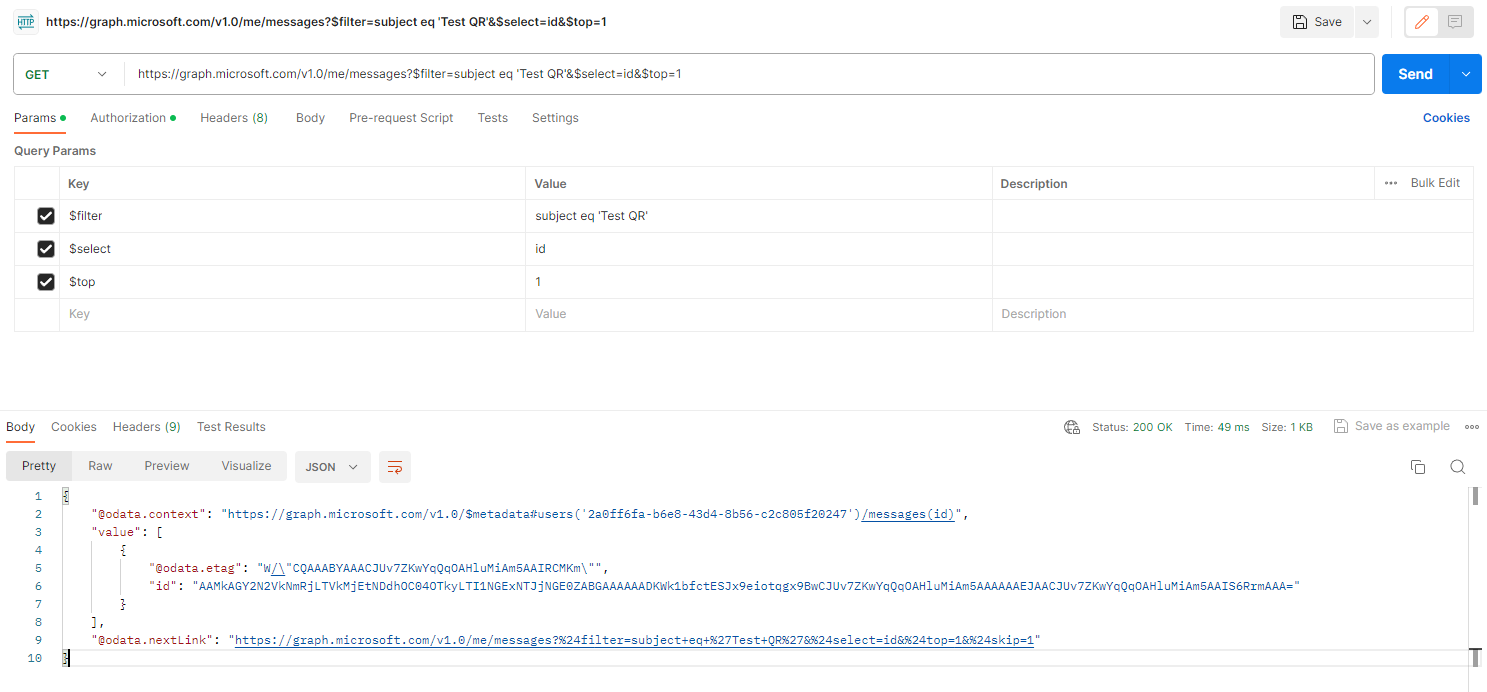

You can now list the messages using the API endpoint and filter for the message id value like so.

Bear in mind that the ID of the email changes when the email is moved to a different folder by the system or by the user. This is why I have included the $top=1 query parameter in the above screenshot and also the summarize max(RecipientEmailAddress) line in the KQL.

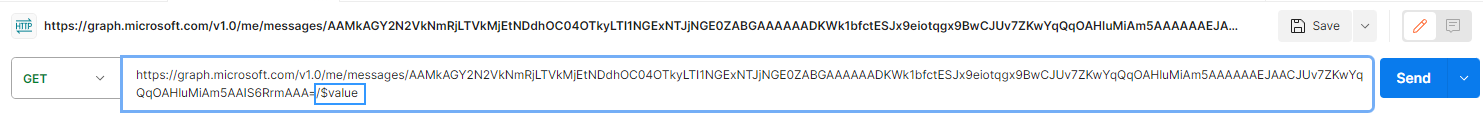

Now that we have the ID we can make the call to the get message API, this API has an incredibly handy feature which allows us to return the MIME content of the email, by using the /$value endpoint. So, our HTTP request looks like this.

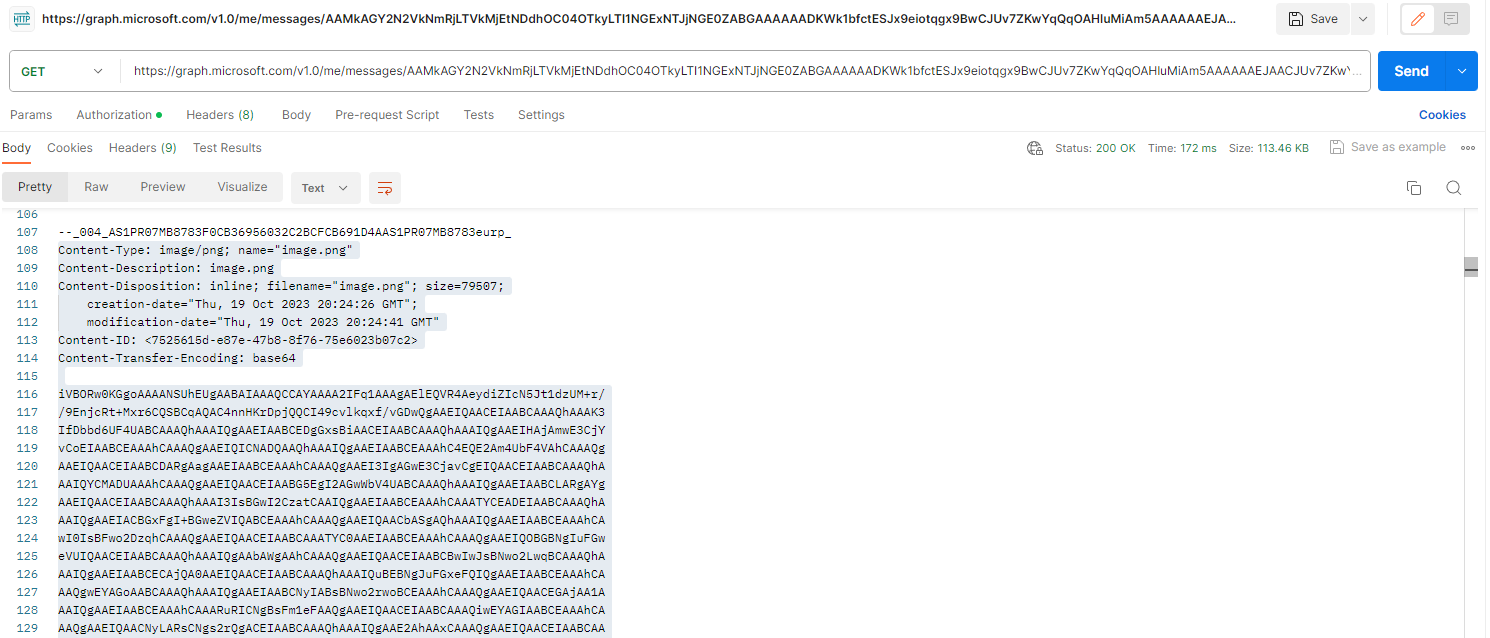

This returns all of the individual content of the email in a base64 format. Included in that format, there is the image we are looking for.

I am unsure if it’s even possible to filter using this API endpoint, but it would be snazzy if it was as then we could return the pure image bytes. Nevertheless, you could just do some filtering on the application side to grab the bytes after the MIME header of the image file.

What’s nice here is that the image file name is the same as what it is in the logs, so you can pull that from your Analytics Rule for some easy filtering.

Processing the image

Now that you have the image bytes you are almost there. When I started writing this article it didn’t even occur to me that there would be an easy way to detect a QR code in an image. How wrong I was. Obviously, there are libraries around to read barcodes and QR codes, people scan them everyday on there phones!

You can just use one of these libraries to read the code. If the code returns data, you have a QR code, if not it’s just some other image.

Using C#, you can read the base64 string into a byte array, which can then be read by a memory stream. The memory stream can then be converted into a bitmap image and read by any barcode library!

A simple code snippet in C# may look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

using System;

using System.Drawing;

using System.IO;

using ZXing;

string base64String = "Some base64 encoded string";

byte[] imageBytes = Convert.FromBase64String(base64String);

using (MemoryStream ms = new MemoryStream(imageBytes))

{

Bitmap bitmap = new Bitmap(ms);

BarcodeReader reader = new BarcodeReader();

Result result = reader.Decode(bitmap);

if (result != null && result.BarcodeFormat == BarcodeFormat.QR_CODE)

{

//The image contains a QR code

string qrCodeText = result.Text;

Console.WriteLine("QR code detected: " + qrCodeText);

// or send the URL off for analysis

//parse the results

//update the incident appropriately using the ARM ID

}

else

{

//The image does not contain a QR code

Console.WriteLine("No QR code detected");

}

}

Taking it a step further

Let’s face it, if a QR code is detected it’s probably going to display a link.

So, once you have decoded the image, your application could even go a step further and run the link against VirusTotal or the likes to determine whether or not it’s malicious.

Going even further, if you pass the Incident ARM ID that your analytics rule generated, you can update the incident in sentinel based off of the VirusTotal result. This means you could auto-close the incident if the QR code is benign, or you could increase the severity of an incident if the URL returns malicious.

Reducing compute power

One final thing I want to mention is how I would probably reduce unnecessary compute power on this application. There are a lot of images in emails, you don’t want to be analysing every single one so here are a couple of things I might do.

- Storing a dictionary of hashes of the already computed images alongside whether they are benign or not. This means you can just do a quick check to see if the hash of the image has already been scanned to see what the result was. You can easily obtain the hash of the attachment from the

EmailAttachmentInfolog table. - Secondly, only analyse images coming from external sources. This is done by adding a filter in the KQL query for inbound traffic.

- Set a limit on the maximum size of the image the app will process. Typically QR codes aren’t massive image files. Disregarding large image files will save compute resources on your function app.

Conclusion

In this article we have highlighted a theoretically possible way to analyse QR codes in emails, using the Microsoft security stack and a custom function application. In the future, I may create a the function application which actually performs this task, but this article has highlighted that this is technically possible.

Although the solution will not proactively block emails, nor is it simple, it does successfully meet the criteria to definitively determine the existence of a QR code in an email. Moreover, it will likely utilise less compute resource than a solution employing artificial intelligence along with image analysis.

Thanks for reading, and feel free to drop me a message on LinkedIn or suggest improvements for the solution!